Tag: united methodist

-

Power Exists to be Given Away – Reminders from Movement Living

Power exists to be given away. The reminder of this came as I listened to the Rev. Dr. Emma Jordan-Simpson preach at the historic Concord Baptist Church of Christ in Brooklyn via podcast last week, in a sermon entitled “Another World.” I hit pause when I heard her words, “It’s that exousia power that we…

-

The Table of Man

At the back of the hotel ballroom, I stood shaking from my encounter with the Spirit. Outwardly composed, the pen I held in my hand betrayed my secret, resisting being steadied each time I tried to set it to the page. I had just stood on the stage with simple straw basket and cup, and…

-

We don’t live on crumbs anymore.

Crumbs. Gathering them used to be the first task of sacred ritual with my mother. I would sweep them into a pile, and off the edge of the table into my cupped hand, while my mother put the teapot on to boil. Brushing them off my fingers into the sink, the dance continued as she…

-

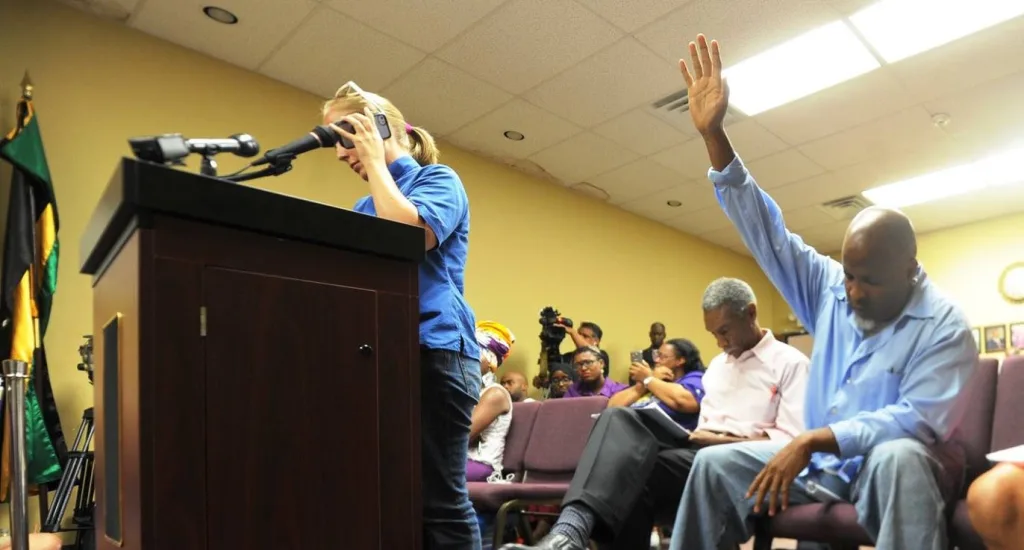

64 Hours for Sandra Bland: The First Night

“You’re going to be arrested tomorrow,” my neighbor said to me solemnly. Sitting on the front stoop of his house, the street was silent. The laughter and mariachi music from the birthday party down the block had long since morphed into a pile of tables and chairs awaiting pick-up. Only a few neighborhood dogs walking their patrol kept…

-

Open Letter To the Sheriff of Waller County

Dear sir, Last night, for the first time, I looked at one of the articles that was written after you told me to “go back to the Church of Satan that you run.” At the time, I’ll be honest, I was aware that there was a good deal of media taking place around your comments…